It’s bigger than teaching, it’s love: How KIPP is getting students to and through college

ByCaroline Bermudez

Read the full article at EducationPost.org >

Read all articles in the series >

Although Nathan Woods was a good student, adjusting to college was difficult. He lost his brother to gun violence as a high-school sophomore and the uncertainties of being a first-generation college student weighed on him. Deceptively minor issues threatened to veer him from the path to graduating.

Improbably, Woods credits his primary school for keeping him on course in college. For years after graduation, Woods’ counselors from his middle school, KIPP DC KEY Academy in Washington, D.C., kept in close touch, encouraging him when the pressure felt so intense he was tempted to drop out.

“There were times I couldn’t afford to get back to college” after break, Woods says. “KIPP teachers would drive me there or back.”

Woods graduated from Syracuse University in 2014. The social support was as critical as his academic preparation in making the difference between finishing college and dropping out.

“I didn’t realize how much that kept me going,” he says. “It’s bigger than teaching. I think that’s love.”

In 1998, the KIPP network of schools created KIPP To College to help students and their families prepare for life after high school. The effort was successful, but it soon became clear that KIPP graduates struggled to finish college. So in 2008, the program was renamed KIPP Through College to emphasize completion rather than just matriculation.

KIPP Through College tackles both the academic and non-academic issues low-income students contend with. It advises students on what classes they should take to be competitive applicants to college and helps their families negotiate financial aid packages. And it addresses the seemingly small, often overlooked hardships that can derail low-income, first-generation college students, like Woods’ transportation problems.

Nearly a decade later, it’s clear the program is working. KIPP students are increasingly crossing the finish line. Currently, 81 percent of KIPP alumni enroll in college after graduating from high school. By last fall, 44 percent of KIPP alumni earned bachelor’s degrees a decade after completing eighth grade—higher than the 33 percent of adults nationwide who earn bachelor’s degrees and more than four times higher than the number of low-income students who finish college.

A charter school network started in 1994 by Mike Feinberg and Dave Levin, two former Teach For America teachers, KIPP has taken on a role few K-12 schools have attempted: to be an institution that increases the number of students from low-income families of color who graduate from college.

This means blazing a trail where not much of one exists. While colleges slowly show signs of improvement in recruiting socioeconomically diverse students, progress has not kept apace with changes in the country’s demographics.

A handful of nonprofit organizations help first-generation students, including the Posse Foundation and QuestBridge. But these groups only work with high-school juniors and seniors who either are nominated by their schools or apply.

“We’re going through a powerful and exciting time in our history where a little over half of our kids in America are kids of color,” says Richard Barth, president of the KIPP Foundation. “As a general rule, higher education has not prepared itself for these dramatic shifts.”

THERE’S SUCCESS BUT THE GAP IS STILL THERE

Nathan Woods is hardly an isolated case study of KIPP’s success. Yet as more Americans than ever are earning college degrees, a yawning gap remains between affluent and poor students in college graduation rates.

According to a report from the University of Pennsylvania, the Council for Opportunity in Education, and the Pell Institute for the Study of Opportunity in Higher Education, 24-year-olds from the highest fourth of household incomes (families earning at least $116,000) comprised more than 50 percent of all bachelor’s degrees awarded in 2014. Students from the lowest quartile, those earning less than $35,000, represented only 10 percent.

Set these disconcerting figures against a backdrop of harried, overworked admissions officers under pressure to read thousands of applications on tight deadlines, the fierce competition among colleges to maintain their selectivity, and the need to enroll enough affluent students to generate revenue, and the manifold obstacles low-income students already face appear impassable.

The deck is stacked in favor of kids who can afford to play the game. They can visit schools, pay application fees and even hire private college counselors for thousands of dollars. Well-off students can turn every wrinkle in the application process to their advantage.

For example, according to a recent article in The Atlantic, nearly half of colleges accept a high number of students via a process known as early decision where applicants agree to attend a particular school in exchange for expedited consideration. Many elite schools admit half their freshman classes via early decision.

But the cost is too steep for low-income students, who typically must wait to compare financial-aid packages from different schools. Competitive colleges also look for signs of a student’s interest in their institution. Never mind that campus visits are often financially prohibitive for low-income applicants.

These problems are further compounded due to the lack of college counselors in high schools. On average, American schools have one guidance counselor for every 500 students. Students in impoverished high schools are nearly twice as likely as students in wealthy schools to have no access to counselors. Thus, students most in need of information and advice on applying to college usually do not get it.

As if the road to college isn’t hard enough for this population, social capital is another hurdle to clear. Non-academic factors—winning friends and influencing people, making professional connections—can be a major determinant in how well a student fares in college and beyond. It is the lingua franca of affluence, a language poor students are largely not privy to. They need to be taught not only how to get to college, but also how to do college.

“Even our kids who go to the most selective colleges,” says Barth, “they still don’t come from a world where they have the networks.”

Although money is still presumed to be the primary hurdle, the reasons low-income students drop out of college are more than financial. Emerging research points to the importance of social factors in college success. A working paper from the National Bureau of Economic Research found that social support helped improve the academic performance and graduation rates of poor students in North Carolina through the Carolina Covenant program. When these students also had access to faculty, staff or peer mentors and workshops on skills such as time management, note-taking, career development or even etiquette, graduation rates rose by 8 percentage points among eligible students.

If the Carolina Covenant program shows this much promise by reaching out to low-income young people already in college, it stands to reason the impact could be much greater if similar programs start years earlier in kids’ lives—which is the basis of KIPP’s theory of action and why Nathan Woods felt comfortable asking his former teachers for rides to Syracuse.

A SOBERING WAKE-UP CALL

Woods’ history with the charter school network stretches back to 2002, when he entered KIPP DC KEY Academy, in Washington, D.C., as a 10-year-old fifth grader. College was a foreign concept to him.

“I heard about it, I saw it on TV, but I didn’t know what it was,” he says.

But on his first day at Key Academy, one sentence altered his perception of himself and what he could achieve: You will go to college in 2010.

“That changed my life,” he recalls.

Despite entering Key behind academically, Woods eventually graduated at the top of his class and won a full scholarship to Woodberry Forest School, a boarding school in rural Virginia. KIPP maintained its ties to him throughout his high school years as part of KIPP To and Through College.

Yet building long-term relationships with students like Woods didn’t immediately yield the results KIPP hoped for. In 2011, the school network issued a report finding that 31 percent of its early-generation middle-school students earned bachelor’s degrees within six years.

Although the figure was well above the numbers reported in the Pell Institute study, KIPP was disappointed by the findings. Jane Dowling, executive director of KIPP Through College at KIPP NYC, called it a “sobering wake-up call.”

After having done the yeoman’s work of getting their students to college, it was hard to hear the uncomfortable truth of what happened when they got there. “Many people didn’t want to come out in the open as to what was happening to first-gen kids,” Barth says.

Although it delivered a black eye, the report was also a boon. It prompted KIPP to rethink its approach to college counseling. Selecting a college can be an emotional process guided more by heart than head; KIPP realized it needed a systematic approach to the whole endeavor.

Staff began staying in touch with students after eighth grade, regardless of whether they attended a KIPP high school or school outside the network. To prepare students and their families for college, especially low-income families, the last two years of high school are too late, says Barth.

“For many of our families, the idea of going out of state is a tough one,” Barth explains. “Particularly with Latino families, they’re very oriented towards the family, people staying home, folks being able to contribute back to the household income. It’s a big issue.”

“To have that conversation with a family for the first time in January of senior year of high school, it’s bordering on unacceptable,” he continues. “We need to start earlier with families on getting them engaged as partners in how this process is going to work and what it might mean for them.”

By junior year, students are expected to have wishlists and hold lengthy conversations with counselors about fit, visiting schools and potential careers.

Through daily data analysis, KIPP high schools across the nation can see where they are in their college guidance work relative to one another: which students need to take the SAT or ACT again, students’ course selections, what students need to do to improve their grades, the number of seniors who have applied to at least six colleges, what financial aid packages students have received from schools and the schools’ average costs.

“How you go about the college application process can be worth 5 to 10 points in college graduation rates,” says Barth. He is blunt about how he wants students and their families to approach applying to college: to attack it like the middle class. KIPP insists students apply to a mix of reach, middle and safety schools, and prioritize fit over feel or name recognition.

Notably, the report also pushed the network to place greater emphasis on not only getting students to college, but shaping where they choose to go to college.

The College Match program is a key component of KIPP Through College. The more rigorous the college, Dowling notes, the higher student completion rates tend to be. To that end, KIPP uses Barron’s, which collects data from colleges specifically regarding the rate of completion within six years for first-generation students. When KIPP identifies colleges graduating these students in high numbers, it approaches the schools to determine whether they are willing to create peer networks for KIPP kids.

KIPP establishes points of contact within each partnering college, be it a dean of student affairs or a student life director, who ensures KIPP students receive the support they need to thrive once they arrive on campus. The partnerships include summer opportunities and working with counselors.

To date, KIPP has formed partnerships with 83 colleges that want to recruit and support KIPP students. Twenty-three percent of KIPP graduates are enrolled at a partner college. Popular schools include Brown, Duke, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, the University of Pennsylvania and Vanderbilt.

Barth lauds other partners like Georgia State, considered to be a model among colleges for using data to increase the graduation rates of low-income students. Through the Panther Retention Grant program, Georgia State awards small grants to financially-strapped students before they have to ask.

THE WORK AHEAD

Another challenge KIPP identified in its rethinking was the “summer melt,” students who are accepted to colleges but who never set foot on campus. Summer melt used to account for 35 percent of KIPP students in New York, Dowling says. The number has dwindled to 2 percent.

Through talks with students who experience the summer melt, KIPP discovered that while they felt academically ready for college, they got lost in the finer details. Non-cognitive factors such as adjusting to being away from home for the first time or managing money, Dowling says, were problems. So KIPP added another layer of counseling.

Once students get acceptance letters, they go through a 35-point checklist covering essentials such as housing and health insurance with counselors. KIPP alumni are brought in to chat with seniors to discuss their college experiences.

Most important is instilling a sense of self-reliance in students. While KIPP students receive intensive help from teachers and counselors, ultimately they must learn to be independent.

“We can’t do everything for our students. The name of the game is curating the information we give to our students,” Dowling says. “We want to teach them to get resources themselves.”

These hard-learned lessons are paying off. In 2013, only 10 percent of KIPP seniors applied to six or more colleges. Last year, 54 percent did so.

Still, a recent survey of almost 3,000 alumni found challenges remain for KIPP students in college. They have trouble landing internships related to their career hopes, securing work-study jobs, and often go hungry in order to pay for books (hunger is a growing problem among college students nationwide). In August, KIPP will hold its second-annual KIPP College Partner Convening to address these problems.

As KIPP leaders learn, they hope to share their discoveries with schools outside of the network. “Nothing we do is proprietary, we’d share it with anyone,” Barth says. “I hope this is something the whole country gets better at.”

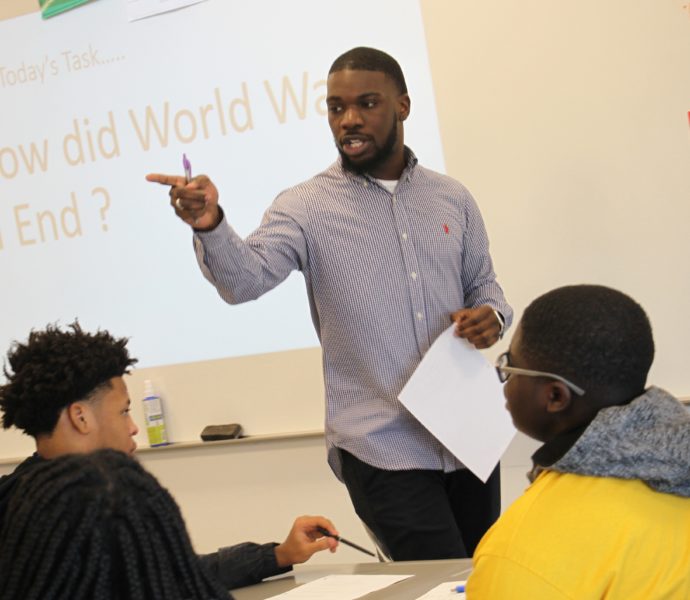

Woods, now 24, is paying forward what KIPP has done for him. After college, he became a classroom teacher in San Antonio through Teach For America. He has since returned to the Washington neighborhood where he grew up, Anacostia, to teach 10th-grade world history and 11th-grade U.S. history at KIPP DC College Preparatory.

He also plays a role in the program that allowed him to overcome his struggles as a first-generation college student. As a KIPP ambassador for Syracuse, he helps students prepare for internships, organizes resume workshops, and finds people at his alma mater who can be sources of information and advice for KIPP students once they land on campus.

Woods, like the KIPP teachers who gave him those much-needed car rides to Syracuse, says he wants to help students from similar circumstances make it to and through college.

“This isn’t just a me thing,” he says, “but a generational thing.”